Alibaba's impending breakup into six different companies sheds light on the valuation of conglomerate firms. The Chinese e-commerce giant is splitting into six distinct firms: Cloud Intelligence Group, Taobao Tmall Commerce Group, Local Services Group, Cainiao Smart Logistics Group, Global Digital Commerce Group and Digital Media and Entertainment Group.

So the result would be firms focused on domestic e-commerce, cloud computing, international e-commerce and media, among others. The smallest unit might be conceptually related to X lab, Alphabet’s development unit. And there would be firms focusing on food delivery and logistics.

Even as Alibaba carries a single valuation figure, no matter which metric is used, each of the six lines of business has a different set of potential metrics, based on existing market evaluations of media, e-commerce and cloud computing, for example.

source: Reuters

A sum of the parts valuation of the broken-up Alibaba, using a price/sales method, might

Value Alibaba's core e-commerce business at $100 billion, while the cloud computing business is valued at $50 billion.

The media business might be valued at about $25 billion, while the logistics unit is valued at perhaps $15 billion.

Using an EV/EBITDA method, Alibaba’s e-commerce business might be worth $250 billion, while the cloud computing business is valued at $100 billion.

The media business might be worth about $50 billion, while the development unit is valued at about the same level.

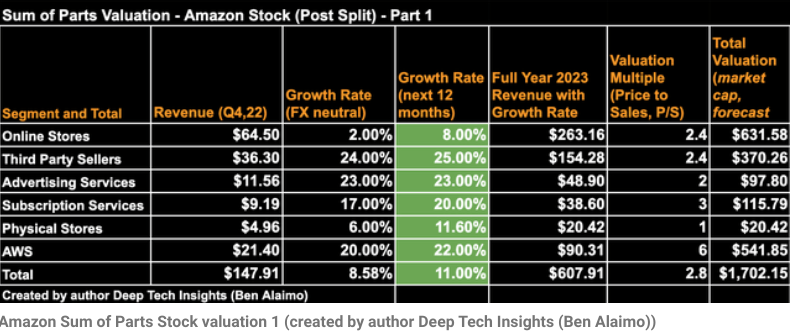

One might make the same observation about Amazon, which might be broken out into perhaps six distinct lines of business, each presumably also potentially valued differently from the other components. Growth rates, also a key factor in valuation, also differs wildly, from the online e-commerce growth rate of about two percent to the 20 percent growth of Amazon Web Services, 23 percent growth rate of advertising and 24 percent growth rate of third party fulfillment services.

source: Deep Tech Insights

source: Deep Tech Insights

Some, such as Ben Alaimo of Deep Tech Insights, would value the e-commerce operations at a price/sales ratio of 2.4, while AWS is valued at a six times P/S ratio, for example.

Other valuation metrics might include free cash flow generation, enterprise value or discounted cash flow. In 2022, for example, AWS might have had an EV/EBITDA ratio in the range of 43, while the rest of Amazon carried a ratio closer to 21.

In 2022, AWS produced about $53 billion in free cash flow, while the rest of Amazon produced perhaps $14 billion.

In 2022, AWS produced a bit more than twice the discounted cash flow as did the rest of Amazon.

Alibaba's cloud computing operations do not produce as much value for that firm as Amazon Web Services does for Amazon. Cloud operations represent about nine percent of total revenue for Alibaba, while AWS constitutes about 16 percent of Amazon total revenue.

AWS arguably represents all of the profit for Amazon, while cloud computing drives about 24 percent of Alibaba profit.

Cloud computing revenues are perhaps 22 percent of Microsoft revenue. It is unclear to me what percentage of profit cloud computing contributes. Google's cloud operations generate perhaps nine percent of total revenue, and nothing (yet) to Google profits.

The point is that many firms in the media, software, online services and data center or access businesses are functionally conglomerates, with lines of business with distinct growth profiles, revenue contributions and profit margins.

Blending all those sources shows the possible value of creating new pure play assets.