So-called “fair share” payments by a few hyperscale app providers to internet access providers in Europe means a formal end to network neutrality as well. Recall that the fundamental net neutrality principle is “non-discrimination.”

At its core, net neutrality means ISPs must treat all internet traffic equally, regardless of the source, destination, content, platform, or application. That has, in practice, meant no blocking, throttling, or prioritizing specific content.

By definition, taxing traffic from a few hyperscale app providers--delivered at the request of the ISP’s own customers--is unequal treatment by source, content, platform and application.

Granted, the flow of revenue within a value chain can take many forms. But the core principle in the communications business has been that customers pay for their own consumption. The possible new European Union rules on “fair share” shift the revenue flow, allowing ISPs to charge both their own customers as well as a few firms whose products their customers use extensively.

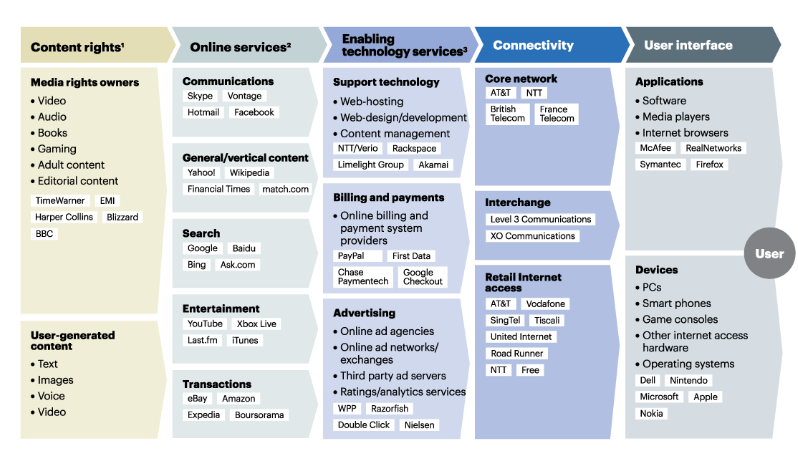

At a high level, digital infrastructure value flows toward end users and retail customers, while revenue flows from end users back to infra suppliers.

Content value is more complicated, as are revenue mechanisms. Some professional content creators create value that flows to distributors, and then to consumers. Revenue can flow from end users, advertisers and other business partners towards content creators and distributors.

E-commerce providers create value that flows up from product creators and suppliers towards consumers. Revenue flows from buyers to sellers and distributors.

Providers of social media and search functions create value that flows to end users. Revenue flows from advertisers and business partners towards the social media and search providers.

source: Kearney

The change in connectivity value might remain relatively unchanged if the EU imposes “fair share” requirements. End users might still be able to access their favored “fair share” apps. But changes always are possible. In the EU, surcharges or fees for some features could develop, as the affected app providers move to maintain their profit margins.

The affected firms might optimize their platforms to minimize data consumption, which could affect user experience. They could shift resources and investments away from the EU, focusing on markets with less stringent regulations.

The affected companies might raise advertising costs for their partners.

The affected firms might explore new data monetization methods. Subscription models for specific features or content could develop.

Overall, the affected firms would likely accelerate an exploration of alternative and additional new revenue streams to compensate for the new costs of doing business in the EU.

Advertising on EU-consumed content might increase. For-fee elements of service could increase.

The point is that no value chain participant, facing higher costs from one of its suppliers, is going to sit still. At the very least, new efforts will be made to offset the higher costs.

In principle, the proposed new payments are a tax on doing business in the EU. And, like all taxes, they are simply a cost of business whose costs must be recovered. They will be recovered. And the payment burden will ultimately fall on consumers and business partners.