Does Long Term Evolution change user behavior? And if so, does behavior change in ways that help mobile service providers make more money? Also, could the substantial use of public Wi-Fi lessen as users shift Internet access back to the mobile network?

A study by U.K. service provider EE suggests some behavioral changes are happening. Basically, the faster 4G speeds seem to encourage people to use the mobile network more, and public Wi-Fi networks less, for access.

To the extent that use of 4G involves a price premium for identical usage cap plans, service provider revenue is, by definition, higher on 4G, compared to 3G.

What is not yet clear is the potential creation of important new revenue-generating apps.

It does appear that 4G users on EE’s network are using both public Wi-Fi hotspots and home broadband services less. In April 2013 about 27 percent of respondents surveyed said they did not use public Wi-Fi, or were using it less.

By the end of July 2013, about 43 percent of respondents indicated they were using public Wi-Fi less.

Likewise, where in April 2013 about 21 percent of respondents indicated they were using their home broadband (fixed connection) less, by the end of July 2013 23 percent of the 4G users reported using the fixed connection less.

Those trends--less use of public Wi-Fi and less use of at-home fixed connections--could have implications for average revenue, beyond any price premium paid for a 4G plan, compared to a 3G plan.

As users find their 4G connections more useful, they might start using more data on the mobile network, compared to public Wi-Fi and fixed broadband. That could encourage users to buy larger usage plans, which would generate more revenue for mobile service providers.

At the very least, that could mean heavier reliance on mobile broadband access, compared to Wi-Fi access. At a larger level, there could be implications for mobile broadband substitution of fixed network access.

A pattern of lower usage is one indicator of possible customer churn.

The study also shows people are sharing videos and pictures over 4G, leading to network upload traffic overtaking download traffic at key events. Think of the example of people at a sports event or big concert. This is another example of “faster speed” changing behavior.

Also, the study suggests 33 percent of 4G users stream more video over 4G than

they did using 3G, with BBC iPlayer, Netflix and Sky Go the favourite TV services.

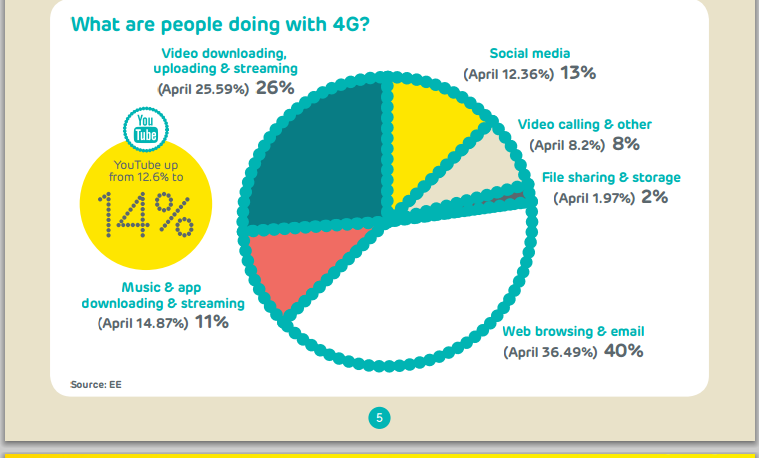

On the other hand, people are using some apps less. The study shows a drop in music and app downloading and streaming, for example. Where in April about 15 percent reported music or app downloading or streaming, just 11 percent did at the end of July 2013.

What isn’t completely clear yet are behavior patterns on smart phones and tablets.

Though people seem to browse the web on 4G phones as much as they do on a fixed connection, streaming patterns on tablets diverge from fixed network behavior.

In other words, iPhones get used all day, while tablet usage rises to a peak in the evening. “The pattern of 4G is generally more variable than 3G,” EE reports. “We also see bigger relative peaks on the commute home and in the evening, largely because of streaming activity.”

“4G is being used at peak times for data-intensive activity, such as streaming, social media activity and apps that makes the most of 4G speeds, EE says.

Though most of the attention will be paid to ways traffic shifts between Wi-Fi and mobile networks, use of tablets also is an issue. Since many tablet users routinely rely on Wi-Fi only as their access method, any greater use of mobile network access will translate into revenue for mobile service providers.

It will come as no surprise that the notebook or desktop computer is used most heavily on an at-home fixed broadband network. But tablet use of at-home roughly mirrors PC usage patterns.