One often hears it said these days that one impact of Covid-19 on organizations and firms is that it will cause permanent changes in the ways businesses and organizations work. Most of those changes, though--agility, reaction speed, cost reduction, productivity changes, customer focus, innovation, operational resiliency, growth, financial performance, for example--were important organizational objectives before the Covid-19 pandemic.

Even remote work on a full-time, part-time or episodic basis is a trend decades old, if many believe the difference is that a large percentage of information workers will shift to permanent remote work settings, and a larger number of observers might agree that many information workers will routinely work more often from home.

One might note that very few of the key changes executives now say they have--because of their experience with the pandemic--can be addressed directly by better or more use of communications services. A recent survey by McKinsey found that “speed” was the driver of organizational changes related to Covid-19.

source: McKinsey

What is not so clear is how much actual change has been accomplished, as organizational change normally is very difficult and also takes a long time. Consider the extensive changes needed to increase speed and agility.

Organizational silos, slow decision making, and lack of strategic clarity, for example, are impediments to speed. But do you really believe that big firms have been about to abolish silos, speed up decision making and gain new strategic clarity in a few months' time?

Big barriers exist for real reasons. If they were easy problems they would have been fixed long ago. Few would doubt that executives say these long-standing issues are being addressed. But also, few of us might believe real progress is being made, fast.

source: McKinsey

Rigid policies and formal hierarchy also are cited as impediments to speed. Have you heard of massive reductions of top level and mid-level management over the past few months?

Or consider the impressionistic claims some might make. “Higher meeting attendance and timeliness” resulted in faster decisions,” one survey respondent says. Do you really believe that? More people in meetings produced faster decisions? Much of the literature specifically argues that more people in meetings. reduces decision-making ability.

It might be fair to hypothesize that meetings, as such, have had no discernible impact. Does anybody really believe holding more meetings improves output? In fact, there is evidence tot he contrary: more meetings mean less time for getting the actual work done.

A team of researchers said this: “We surveyed 182 senior managers in a range of industries. 65 percent said meetings keep them from completing their own work. 71 percent said meetings are unproductive and inefficient. 64 percent said meetings come at the expense of deep thinking. 62 percent said meetings miss opportunities to bring the team closer together.”

Another leader notes that “communication between employees and executives has become more frequent and transparent, and as such, messages are traveling much more efficiently” through the organization.

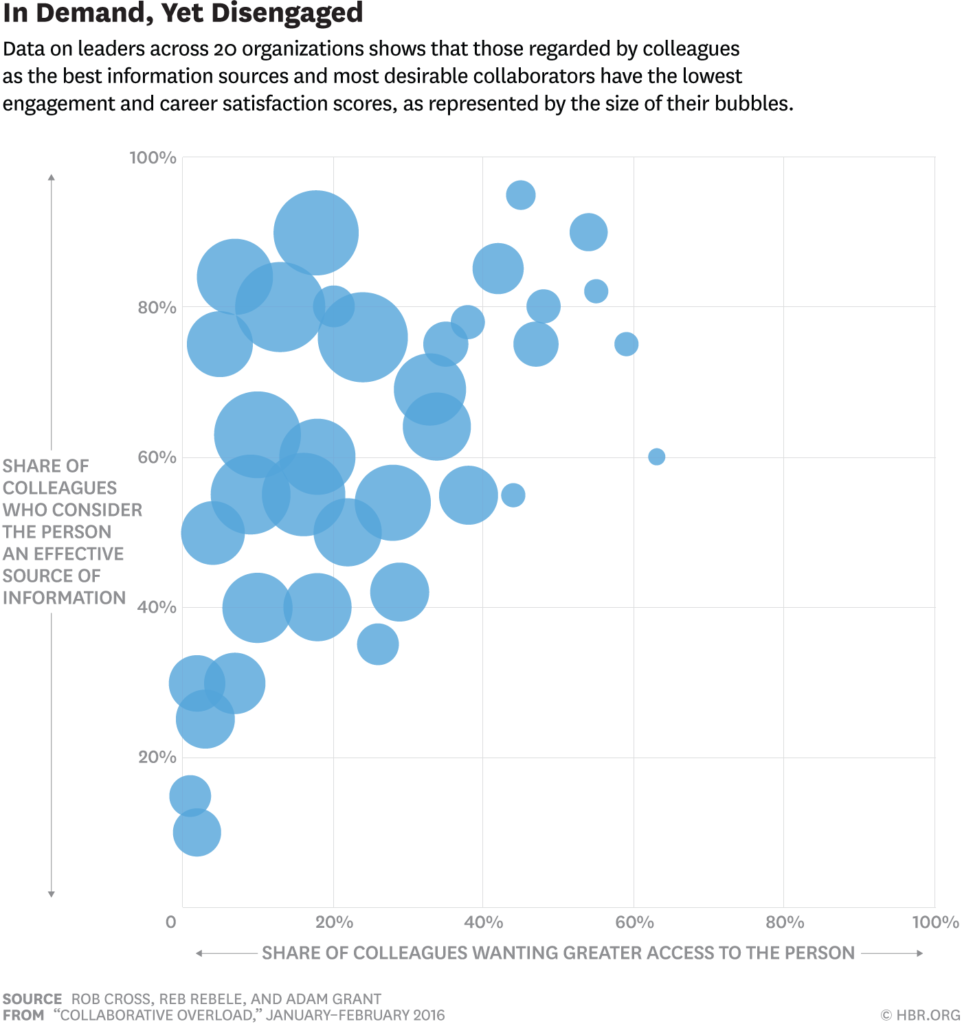

There already are signs of what might be called collaborative overload. “In most cases, 20 percent to 35 percent of value-added collaborations come from only three percent to five percent of employees.

Colloquially, that proves the truth of the observation that “if you want something done, give it to a busy person.” The practical observation is that the highest performers are besieged with the greatest amount of demand for time spent in meetings and on work teams. At some point, the danger is that these high performers simply get asked to do too much, reducing their overall contributions and effectiveness.

source: Harvard Business Review

Not to belabor the point, but value--assuming the insight is correct--can be gleaned by having many fewer people in meetings.

Nor, for that matter, is it entirely clear how greater numbers of team members working remotely actually addresses any of those aforementioned issues. Some changes could materially impact performance in a positive way. But the issue is how remote work, for example, materially abolishes silos, speeds up decision making, produces strategic clarity, abolishes rigid policies or reduces hierarchy.

Some will argue that “employees like it.” The more accurate statement could be that “some employees prefer work from home, and some do not prefer it.” But productivity is not a matter of what people believe. It is a matter of fact, to the extent we can measure it.

Productivity. is often hard to measure--perhaps almost impossible for information workers--and employees claiming they are productive does not make it so. Also, what we can measure might not actually correlate well with actual output. Quantity is not quality, in other words. Innovative ideas and creativity might not be measurable at all, except by reputation.

Productivity measurements in non-industrial settings are difficult, as it often is difficult to come up with meaningful quantitative measurements that provide insight. We might all agree that not all tasks create the same value for any organization. Productivity can be described as the relationship between input and output, but “output” is tough to measure.

And what can be measured might not be relevant.

Even some who argue work from home productivity is just as high as “in the office” note that work from home productivity is only one percent lower than in the workplace.

Some argue productivity now is higher or equal to productivity when most people were in offices. Some of us would argue we do not yet have enough data to evaluate such claims or evaluate the sustainable productivity gains. It is one thing when all competitors in a market are forced to have their work forces work from home.

It will be quite something else when WFH is a business choice, not an enforced requirement. As might be colloquially said, widespread WFH will last about as long as it takes for a key competitor not working that way begins to take market share.

Not to deny that post-pandemic, some firms will find meaningful ways to restructure business processes to gain agility, productivity and speed, but the actual gains will be slower to realize than many expect, as organizational resistance to such changes will be significant. Resistance to change is a major fact of organizational life.